—Poems by Kimberley Bolton, Jefferson City, MO

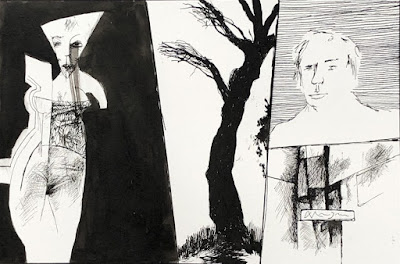

—Artwork by Norman J. Olsen, Maplewood, MN

—Artwork by Norman J. Olsen, Maplewood, MN

THE NIGHT BEFORE HE LEAVES

1845

After supper he went off by himself.

He could hear the voice of the river

calling at twilight to the creek rushing

toward it, like a mother calling

a child home at the end of day.

He tramps along the stream’s edge,

rifle crooked under his arm.

The deep dark of the heaven with

its uncounted stars hangs over him.

The air heavy with the sweet rot

of the woods.

He walks between the tall, bleached-white bark

of the sycamores, the silent, stalwart oaks.

Overhead an owl demands who? Who?

But the man knows himself too well

to have to explain himself or his presence here

to the lone nocturnal bird.

He is a man of the land and the land he stands on

in holy solitude is his own.

The pleasure of that conviction has worn a groove

deep into his soul,

the way the creek has carved its natural groove

into the earth.

He thinks of the hard journey that lies ahead.

The distance he must put between himself

and this life he has made along the banks

of Grindstone Creek.

Already he misses it: the farm, his children,

his woman, his sense of peace giving way

to the intrusion of unwanted obligation.

He turns back toward the cabin.

A soft misting rain patters down

through the leaves.

Faintly, among the trees, he sees

the yellow glow of the lantern she’s left

in the window to guide him home.

After supper he went off by himself.

He could hear the voice of the river

calling at twilight to the creek rushing

toward it, like a mother calling

a child home at the end of day.

He tramps along the stream’s edge,

rifle crooked under his arm.

The deep dark of the heaven with

its uncounted stars hangs over him.

The air heavy with the sweet rot

of the woods.

He walks between the tall, bleached-white bark

of the sycamores, the silent, stalwart oaks.

Overhead an owl demands who? Who?

But the man knows himself too well

to have to explain himself or his presence here

to the lone nocturnal bird.

He is a man of the land and the land he stands on

in holy solitude is his own.

The pleasure of that conviction has worn a groove

deep into his soul,

the way the creek has carved its natural groove

into the earth.

He thinks of the hard journey that lies ahead.

The distance he must put between himself

and this life he has made along the banks

of Grindstone Creek.

Already he misses it: the farm, his children,

his woman, his sense of peace giving way

to the intrusion of unwanted obligation.

He turns back toward the cabin.

A soft misting rain patters down

through the leaves.

Faintly, among the trees, he sees

the yellow glow of the lantern she’s left

in the window to guide him home.

CALL TO ARMS, 1863

Lots of folks hereabouts knew Albert Hornbeck.

He was a homeboy from over in Cooper County.

Had him a little farm up around Prairie Home.

After Claiborne Jackson’s first call to arms in ‘sixty-one,

Hornbeck joined up, servin’ the Stars and Bars.

Nobody thought less of him fer it.

Just as we didn’t think less of any family in these parts

what was pro-Union.

Live and let live, that’s how we saw it.

They was those of us what stayed out of the squabble

fer near long as we could.

And some, like ole James Larimore,

declarin’ loud and clear it warn’t none of his business,

let others tend to it, if they was of a mind to.

But there come a time, down the road,

when a man had to make his stand.

That time come fer some of us in ‘sixty-three

when Albert Hornbeck, Captain Albert Hornbeck,

showed back up here to recruit friends

and neighbors fer the Confederacy.

Hornbeck had no trouble musterin’

the boys from this part of the county

to serve the cause.

They lined up to make their mark

or signed their name if they knew how,

and was proud of it!

You see, most of ‘em was huntin’ buddies:

Hornbeck, the Redford brothers, and some

of the Hall boys, among others.

They spent many an autumn

down at the ole tannin’ shed,

curin’ hides and passin’ the jug

around betwixt ‘em.

They was young and full of piss n’ vinegar,

as any of their Pas would say,

and they couldn’t join up fast enough

if it meant goin’ huntin’ together again.

Only this time they’d be huntin’ Yanks.

‘Course, it never occurred to any of ‘em

those same Yanks would turn out to be

kin or close neighbors.

Boys just like theirselves they’d growed up with.

Boys whose sisters or cousins they’d

courted er kissed on the sly.

That sorrow would come later.

Onc’t we heard that Hornbeck

was recruitin’ fer the army,

we beat it over to Prairie Home

and scrawled our John Hancocks

or marked our X on the line.

And Lord help us, onc’t we was in it,

we was in it.

THE WAITING TIME

Rhoda waits.

And sweeps the floor.

Rhoda waits.

And stokes the fire.

She waits.

Churns the butter.

Beats the rugs, spins the wool.

Scrubs the clothes on the washboard.

She waits and worries.

Autumn.

Rhoda’s worry blinds her to the woods afire with color after the heavy rains.

Aids her neighbor in delivering a baby over to the next farm.

Sends the younger children off to school each morning.

She waits.

Makes soap from lye and ash.

Stirs the giant kettle of sorghum molasses with the paddle

over a hot fire in the front yard of the cabin.

She waits, her worries deepen.

Sets the boys to butchering the hog for winter meat.

Hangs the bacon and hams in the smokehouse.

Chinks the cracks in the cabin walls before the winter winds

sneak inside.

She waits.

She tasks her girls with hulling the walnuts they have collected from

the stand of walnut trees across the creek bank.

The leaves have come and gone.

She does not notice the bare branches of the trees

scratching at the sky in anguish.

First frost.

The older boys ready the farm for winter

without their father, without a reminder from their mother.

Rhoda waits.

The first snowfall of November.

She mends the children’s clothes.

Darns their socks by the hearth at night

after they have all gone to bed.

She stares into the fire as the worry claws at her insides.

Rhoda waits.

Paces the floor.

Stares out the window.

Looks out at the falling snow.

Rhoda waits.

Pulls her shawl close about her shoulders.

Holds her grieving in.

____________________

Today’s LittleNip:

How is it possible to have a civil war?

—George Carlin

____________________

—Medusa, thanking Kimberly Bolton, for another visit from Jefferson City, MO, and thanks also to Norman Olsen for his fine India ink sketches today!

“Rhoda waits . . . and stokes the fire.”

Photos in this column can be enlarged by

clicking on them once, then clicking on the x

in the top right corner to come back to Medusa.

Photos in this column can be enlarged by

clicking on them once, then clicking on the x

in the top right corner to come back to Medusa.